Happy Halloween! Satan, Candy and the Gospel

Why are some Christians so scared of Halloween?

Today is Halloween! Some of you will be planning costumes, or stocking up on candy for trick-or-treat visitors, particularly if you live in the US. Here in Scandinavia, Halloween is a much more recent phenomenon, slowly growing in popularity to rival the local traditions of Allhelgona, but this year will see a Halloween costume parade in Stockholm.

The religious status of Halloween is complicated. Most people today see Halloween as a nonreligious and harmless celebration of childhood, candy and scary stories. At the same time, Halloween does take its significance and symbolism from Christian religion, and it is feared and hated by some Christians.

This blog post will try to untangle that complicated story. We will start with the history of Halloween in Britain and America, look at the American anti-Halloween comics of Jack Chick and the more ambivalent responses of evangelical Protestants, and end by considering what this event can tell us about “religion”, media and going public.

What is Halloween, anyway?

In the English-speaking world, the end of October brings the festival of Halloween. This moment has long been marked by a popular seasonal festival in the British Isles, associated since Celtic times with fortune-telling and visits from the dead. The Catholic Church chose the same date in the 8th century for a festival of “All Saints” (“All Hallows”) and later expanded the celebration to include a second day dedicated to “All Souls”.

In Britain, the 16th-century Protestant Reformation brought efforts to stamp out Catholic holidays, and also saw a new fascination with the evils of witchcraft. The two fears were combined, and the night before All Saints’ Day became known as one of the great gathering times of witches. In 1590, for example, Danes and Scots were accused (and convicted) of plotting against King James VI and Princess Anne of Denmark by working with the Devil on the night of Halloween, throwing cats and corpses into the sea to create a great storm.

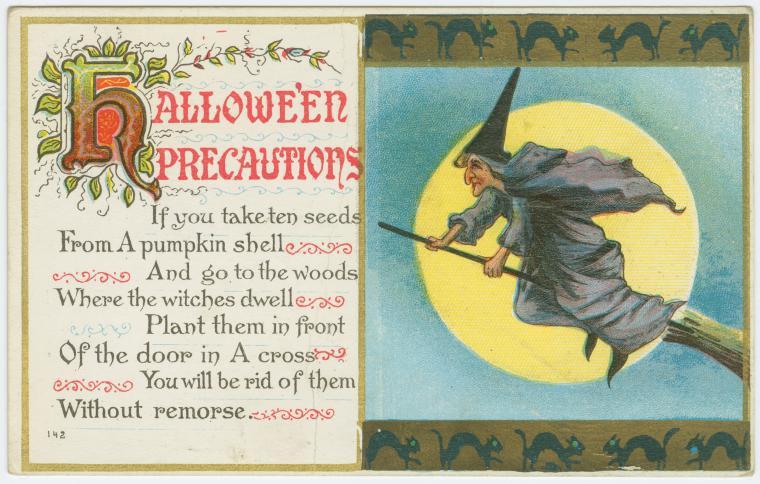

Postcard, America, early 20th century. Source: New York Public Library

In Britain, Halloween was soon overshadowed by the revelries of Bonfire Night (November 5th). In the United States, on the other hand, British immigrants (particularly from Ireland) continued their interest in Halloween fortune-telling and mischief. In the late 19th century, Halloween parties became popular, emphasising monstrous decorations, fortune games and pranks. Public concern about Halloween mischief grew over time, culminating in the “Black Halloween” of 1933, when tales of widespread destruction in US cities led to calls for an alternative. Many towns began to organise their own Halloween parties and “haunted houses” for children, as a more civic-minded distraction.

As Halloween in the US became more associated with children, it also became more commercial. The early 20th century saw the printing of thousands of “Halloween postcards”, which combined familiar imagery of pumpkin heads and witches with stranger possibilities (like the witch-plane you can see below). New industries emerged for the new trick-or-treat market after the 1940s, including children’s costumes and specialist candy.

“Tis Halloween and I’m here again / from the man in the Moon in an Aeroplane /My charms are new and right up to date / To tell by the cards your fortune and fate.” Postcard, America, 1910s. Source: New York Public Library

Fighting Halloween with Jack Chick

Protestant Christians have always been worried about Halloween’s witches. In America, the popularity of Halloween has caused particular anxiety, reviving some of the anti-witch hysteria of 16th-century Britain.

The late Jack Chick (1924-2016) is a good example. Chick was famous for his uncompromising tracts, small comic books designed to warn readers of the dangers of everything from Dungeons and Dragons to Catholicism. A typical tract begins with a scenario that seems harmless, kills off the main character in a shocking twist, reveals the dreadful afterlife that awaits them for rejecting God, and ends with a presentation of the gospel message that could save the reader from such a fate.

For Chick, Halloween was exactly what it appears to be: a festival in which the forces of evil really are at work. In his tract “The Trick”, Chick tries to show that Halloween candy is more dangerous than it seems. In this cartoon, a group of modern-day suburban witches plots to murder their neighbours’ children with poisoned candy. Mid-story, the tale is interrupted when a witch dies of a heart attack and discovers the awful fate that Satan really has in store for them all. The tale has twisted: this secret society is itself being deceived.

After this interlude, the plot returns to the suburbs, where something is wrong with the injured children. Their physical wounds are recovering, but they have become rebellious. A wise “ex-witch” comes to visit to discuss this problem and explains the secret truth of Halloween. In her version, Halloween began with druids, Satanism and human sacrifice, continues today as an annual ritual of murder, and is also “carefully planned by Satan” to persuade humanity that witchcraft is not real at all. The evil witches are eavesdropping, but there is nothing they can do. At the end of the story, faith in Jesus restores the affected children to their senses.

The narrative in this brief cartoon is highly convoluted, reflecting the puzzle that Chick faces in trying to make sense of Halloween: how can this one festival be an actual riot of Satanic witchcraft, and also a silly game for children?

Chick’s solution is to fill his tale with layers of half-knowledge: a supernatural afterworld, a secret society of witches, a cursed family, and a single Christian believer. Everyone in the story knows something, but no one knows everything. I leave it to the reader to decide if this solution is satisfactory, on a narrative or theological level, but it is an interesting demonstration of how complex the epistemology of religious worlds can become.

Postcard, America, early 20th century. Source: New York Public Library

Evangelical Christians and Halloween

Jack Chick represents an extreme in Protestant Christianity, but the concerns he struggles with are widespread. In many evangelical communities in the English-speaking world, Halloween is a time of great confusion. Working out how to engage with this phenomenon is an annual dilemma for Christian churches and families, covered extensively in Christian magazines and news sites.

A recent Christian survey of 1000 Protestant pastors asked for their responses to Halloween. Interestingly, less than 10% wanted to avoid the occasion. Two-thirds preferred to attend an alternative Christian event, like a seasonal “fall festival”, a children’s costume party or a “judgement house” (designed to terrify visitors by revealing what their local church actually teaches about sin and hell). Half of the pastors suggested inviting trick-or-treaters to church, or handing out gospel tracts to trick-or-treaters.

The dilemma over Halloween is also clear in Christian magazines. In 2014, for example, British evangelical leader Krish Kandiah explained to the UK-based website Christian Today that he was finally ready to allow his children to participate in Halloween festivities, after years of reluctance. His article is accompanied by a photograph of a very impressive Jesus pumpkin. However, his tolerance is not unchallenged: in 2016, this same site has reported that witches at Halloween engage in a “shocking ritual of abuse”, lurid claims reminiscent not only of Jack Chick but also of the long-debunked “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s.

Conclusion: Halloween and Religion

So what do these examples show us about religion, media and publicness?

The place of religion in this story is clearly complicated. Halloween combines practices older than Christianity (like fortune-telling and encounters with the dead) with the Catholic festival of All Saints’ Day, and it became popular in Protestant countries driven by a combination of anti-Catholic sentiment and terror of witches. Halloween would not be categorised by most people as a religious festival, and yet it is dedicated to enjoying one’s fear of an “Other” defined almost entirely by religion. Trying to define Halloween as “religious” or “nonreligious” is meaningless, because religion is inextricably tangled with culture, history and everyday life.

These examples also entangle religion with media. Despite revealing Halloween as an orgy of child murder and possession, Jack Chick still encouraged his fans to get involved. His company recommends “sharing Jesus with the kids” by handing out tracts with their trick-or-treat candy, using print media to circulate his Christian ideas. At the same time, Chick tracts are also distributed among non-Christians for their novelty value, like Buzzfeed’s collection of the “7 Best Chick Tracts To Read This Halloween”. Media technologies are used to promote religious ideas, to circulate them in new contexts, and also to make fun of them.

For evangelical and fundamentalist Christians, Halloween intensifies an ever-present tension. On the one hand, these churches tend to insist on clear and unchanging standards of doctrine, including the reality of spiritual forces. On the other hand, they are often keen to engage with popular culture as an opportunity for proselytism. Evangelicals in particular produce new Christian versions of popular fashion, music and entertainment. At Halloween, these opposing desires for theological clarity and public engagement are particularly difficult to reconcile.

In this post, I have tried to show that Halloween is a perfect case study for exploring the relationship between religion, nonreligion, popular culture and media. It is also a great opportunity to see how religious traditions struggle to go public when their values conflict with the expectations of wider society.

Tonight, the future of religious studies research requires at least some of us to wear silly outfits and eat a lot of candy.