Kicking the Saint and Why Material Religion Matters

A Brazilian pastor kicks a Catholic saint to show that icons are lifeless. But just how lifeless are material objects if we find them nearly everywhere in religious worship?

Material Religion?

Many of us think of religion as a system of beliefs—as ideas about the purpose and meaning of this life and the next that motivate our actions. This is certainly a part of religion, but in no way all of it. When the peer-reviewed journal Material Religion launched in 2005 its editors were well aware of the eyebrows they would raise. Reflecting on the progress of the publication a decade later, the editors recall an early response to the journal’s name, “Material Religion? Isn’t that an oxymoron?” Some were surely puzzled. Indeed, at the time religious texts, doctrines, leaders, and institutions dominated studies of religion—and still do, for the most part. But thanks to the diligent work of several brilliant scholars around the globe, ‘material religion’ is today far from an oxymoron; it is an emerging area of research that brings together a diverse group of thinkers. Increasingly, scholars agree that the concept of religion must be expanded to include its material dimensions. In other words, religion isn’t just a matter of belief; it’s also about how matter shapes belief.

Material Religion in Brazilian Neo-Pentecostalism

So what does this material approach to religion actually look like in scholarly research? How has it been applied? For the remainder of this blog post, I will offer some insight into my own research on how religious objects facilitate different power relations. I use the Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, hereafter UCKG)—a global Neo-Pentecostal religion based in Brazil—as a case study. First, I’ll offer some context for understanding Neo-Pentecostalism and the UCKG in Brazil before exploring the role religious objects play in the church.

The Universal Church of the Kingdom of God in Brazil, where the author went to explore the role of religious objects. Photo: Gavin Feller

The term Neo-Pentecostal describes a third wave of Pentecostal churches started in the 1960s and 70s as part of a larger charismatic movement. Neo-Pentecostal churches are generally distinguished by their heavy use of mass communication technologies such as radio and television, their vision of global expansion, and their focus on prosperity theology—the belief that God rewards the faithful with physical health and financial wealth. Currently, Brazil is home to the largest community of Neo-Pentecostals in the world. A man named Edir Macedo, a former Catholic and state lottery employee, devoted his life to the ministry at age 33, founding the UCKG in 1977. The UCKG exploded in popularity. Just 23 years after the church’s founding, the 2000 Brazilian national census recorded a membership of over 2 million (in a country of 174 million at the time). As part of a larger trend, in the last 20 years the percentage of Pentecostals in Brazil grew from 6% to 13% of the population. This growth is even more significant when considering that the percentage of Brazilians who identify as Roman Catholic has plummeted from 95% in 1970 to just 65% in 2010. The presence of the UCKG—alongside other Neo-Pentecostal churches—is therefore anything but unnoticeable. With its ownership of several radio and television channels, the UCKG is highly visible and highly controversial. In other words, though it’s not the biggest religion in country, not by a long shot, its leaders often talk and act like it is!

Kicking the Saint

I’ll turn my attention now to one specific UCKG controversy to segue into the topic of material religion and my study of UCKG objects. In 1995, a UCKG pastor, Sergio Von Helder, physically kicked Brazil’s patron saint, Nossa Senhora da Conceição Aparecida (Our Lady of Aparecida), in a live broadcast televised to millions of viewers…on the public holiday celebrating the saint.

The pastor kicked the three-foot statue to demonstrate its lifelessness to his viewers. “We are showing the people that this doesn't work," said Von Helder. “This is not a saint,” he continued. “This is not God. Could it be possible that God, the Creator of the universe, be compared with a puppet like this, so ugly, so horrible, and so wretched?" Well-known as the largest Catholic country in the world (two-thirds of Brazil’s population identify as such) it goes without saying, the “kicking of the saint” did not go over well in Brazil.

Although Von Helder was removed from his position and Macedo, UCKG’s founder, publicly apologized, the episode gives you a taste of the distaste the church has for religious icon and its penchant for picking fights with other faiths. As a trained media and communication scholar interested in Brazil, the UCKG’s media showmanship and its heated rhetorical attacks on other faiths made for a perfect research project on the intersection of media and religion. My curiosity was further piqued as I began learning about the UCKG’s use of Judaica--ceremonial art and objects used in Jewish ritual. For someone unacquainted with the rising popularity of Judaica in Brazilian Neo-Pentecostal practice and merchandise, I found images of UCKG founder Edir Macedo--beard, kippah, tallit and all--surprising to say the least. Rather than study the UCKG from afar, I was determined to get a better understanding of it by experiencing the world of its everyday followers.

Religious Objects and Power in the UCKG

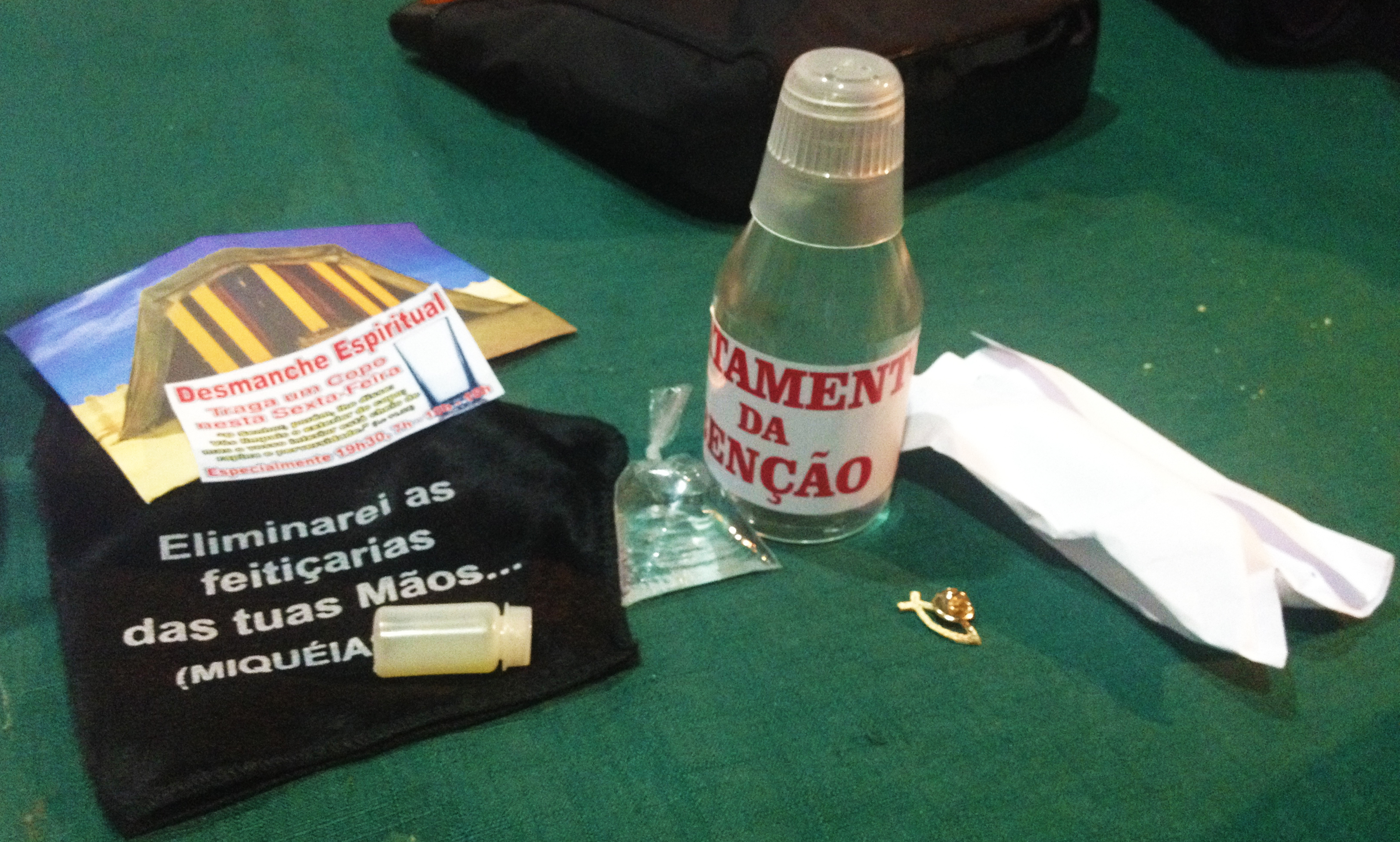

I traveled to Brazil to study the role of religious objects in the UCKG by immersing myself (to the extent possible) in the lives of its followers. In two separate visits, I spent several weeks in Rio de Janeiro, the church’s birthplace, and São Paulo--the new headquarters of the religion and location of its recently constructed Templo de Salomão (Temple of Solomon)-- a $350 million replica of the ancient biblical building. In addition to visiting the awe-inspiring Temple, and its predecessor the Catedral da Fé (Cathedral of Faith) in Rio, I spent the majority of my time observing worship services at several small, local temples, as well as informally interviewing followers. While the size and grandeur of the Temple of Solomon and the presence of Jewish artifacts and symbols was truly fascinating, what surprised me the most was the ubiquity of small, everyday objects in regular worship meetings.

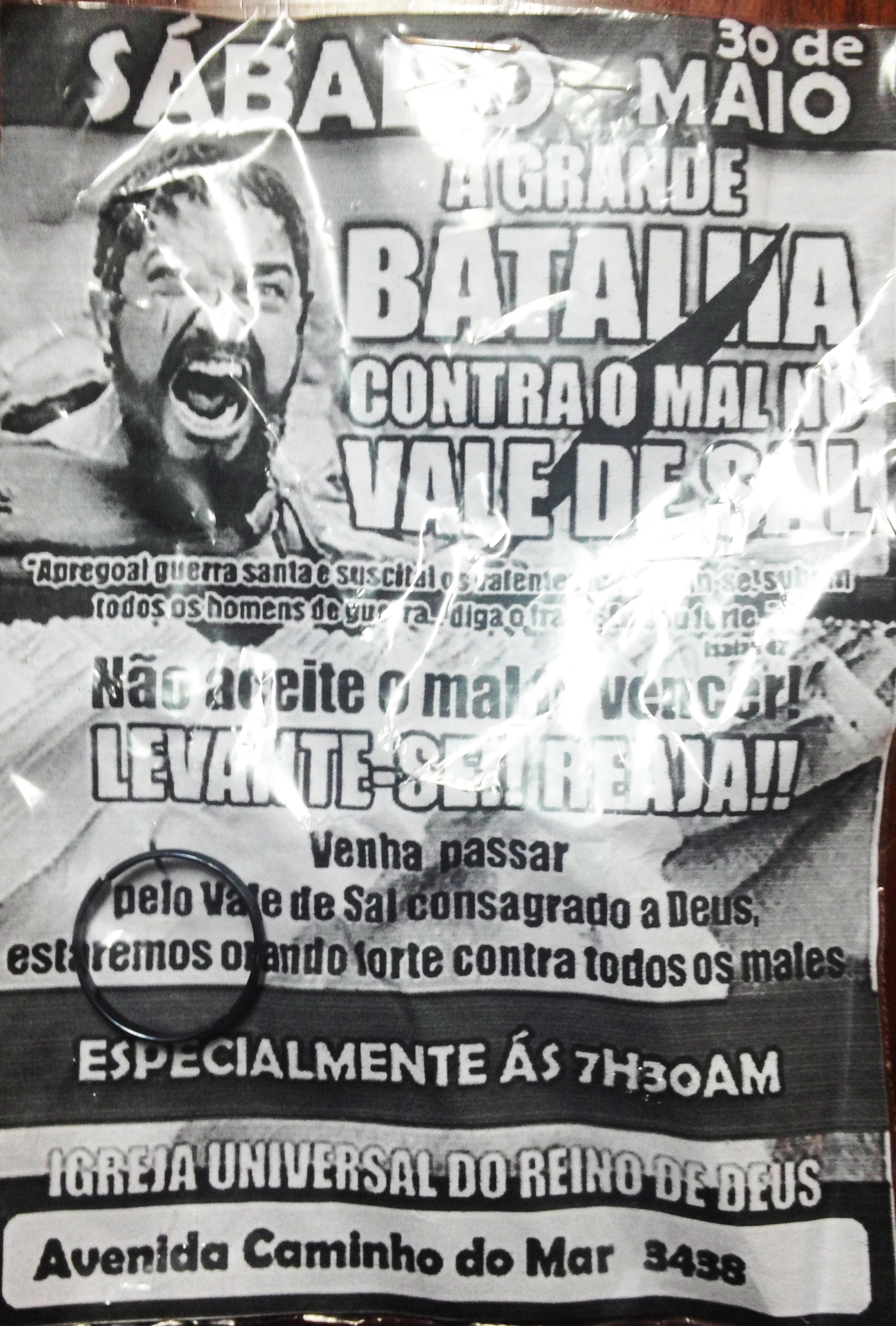

Let me provide some examples of just how integral mundane materiality is to the religious experience of followers of the UCKG. Worship services, held daily, are punctuated by several (as many 6-8) calls to offer--both a tithe and an additional monetary offering. Once followers have given their bills and coins, or in the case of the Temple of Solomon swiped their credit card, they receive something physical in return. Often it’s a drop of olive oil touched to their forehead. Sometimes it’s a handful of salt poured into their palm. Other times it’s a small object such as an envelope or a bracelet or some kind of trinket branded with the UCKG logo. In addition to these objects, other paper flyers and handouts are distributed in anticipation for upcoming services. Once I was given a flimsy metal ring enclosed in a bag with an edited picture taken from the Hollywood film 300: Rise of an Empire.

Photo: Gavin Feller

I was to return to a special worship service later in the week where I would break the ring, and thereby symbolically break my alliances with the evil holding me back from spiritual, financial, and physical health.

(By the way, the word aliança in Portuguese means a covenant or aliance in a religious context and a wedding ring in a civil context--so the ring has a powerful dual meaning.)

UCKG "swag": free and plentiful. Photo: Gavin Feller

Every meeting I attended I left with at least a few pieces of swag, and in some cases as many as eight items to take home. The term swag, as I am using it, is not a curtain or piece of hanging fabric. Rather, swag can be defined as “products given away free, typically for promotional purposes;” “a very confident attitude;” and “a large number or amount.” Each of these definitions, taken together, articulates common characteristics found among the large number and variety of objects given away at UCKG services.

Taking Away…And Coming Back

So what exactly can these objects teach us? They teach us about UCKG power relations. By giving away such a high number of tangible things every meeting, followers collect receipts, if you will, for their monetary offerings. These material ‘receipts’ subtlety reinforce the notion that when you give to God you receive in return. Though small, cheap, and otherwise ephemeral, these objects accumulate. And, as Marcel Mauss- the father of exchange theory- argued, every gift comes with a burden to reciprocate. In this case, the burden often takes the shape of an implicit obligation to return to UCKG services and to continue to give monetary offerings as a demonstration of faith and devotion. So, in this sense, this swag perpetuates the power of the UCKG. Followers remain tied to their local pastor and temple in a perpetual cycle of giving and receiving-- a cycle that, again, taps into a theology of prosperity.

Of course, there is greater nuance and complexity than this post allows. What I have offered is a small sample of the vital role religious objects play in religious life. Previously overlooked by a fixation on belief, material religion is now more popular and useful for scholars than ever. Statues of the patron saint of Brazil are perhaps not so lifeless after all, at least if they’re used strategically by a powerful religious institution. What the faithful physically hold in their hands, wear on the heads, and press close to their hearts is as important--and perhaps more important in some cases--than what they believe in their heads.